Chapter 3 of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is where stuff starts getting good–and by good, I mean, magical!

General Commentary:

This chapter starts us off with yet another thing that’s mentioned offhandedly–yet underscores exactly how badly the Dursleys treat Harry. Which is to say, they keep him in the cupboard until the summer. One has to wonder whether Harry was allowed out to go to school at all. It isn’t stated. And I wouldn’t put it past the Dursleys to just leave him in there. One also presumes Harry snuck out out periodically for food, and just thinking about it cracks my heart for the poor kid.

I’m honestly a little surprised that Aunt Petunia would go to the trouble to actually dye some of Dudley’s old clothes for Harry–which is after all an expenditure of effort on his behalf, which doesn’t seem like her. But on the other hand, I suppose that that would be less bothersome to her than actually paying for a new uniform, so.

Fortunately, things are about to look up.

The arrival of the first letter from Hogwarts is enticingly mysterious, and I love the description of the parchment and the emerald-green ink. The letter as a physical object, all by itself, is therefore far outside the norm of what Harry’s used to, and a lovely little hint that we’re only getting started here. It’s particularly telling how the Dursleys know what’s going on, too, given how Vernon and Petunia both react to the coming of the first letter.

Dudley’s second bedroom is another very telling description of how repulsive the little brat is–with all the broken things he doesn’t take care of abandoned to be stored in there, far more things than the Dursleys will ever be bothered to give to Harry. It’s noteworthy as well that the books in the room are described as the only things that look like they’ve never been touched, which leads one to wonder whether Vernon and Petunia tried to buy books for their kid, whether they’re his schoolbooks, or what. Dudley certainly is never described as the sort who’d want to crack open a book on his own recognizance.

And it’s only with the threat of the wizarding world about to discover them that they allow Harry to sleep in that room at all, rather than leaving him in the cupboard, for that matter. Just in case you’ve forgotten that the parents are as repulsive as the child.

It’s this threat, too, that drives Vernon to stay home from work two days in a row to nail up the letterbox AND to seal the doors, all in the name of trying to keep the letters from reaching Harry. And then he whisks them all off to try to evade the letters entirely–which of course does not work.

We’re not told whether Vernon got into any trouble with his job with this going on, or if he called in sick or claimed to have a family emergency or what. One does really rather hope he got chewed out by his boss later on.

I’ve just recently re-watched the first movie, and one of the things that gets glossed over in the film is how the letters escalate in frequency and number, and how they keep changing addresses as well as Harry’s location changes. Plus, the way the letters arrive gets increasingly weird. I adore the description of some of them showing up in the eggs:

Twenty-four letters to Harry found their way into the house, rolled up and hidden inside each of the two dozen eggs that their very confused milkman had handed Aunt Petunia through the living-room window.

That sentence all by itself is a small gem of detail about how Rowling’s world works.

And, of course, Vernon whisks the family off on the desperate and unsuccessful quest to avoid the letters, while Dudley whines, a storm rages–and Harry realizes it’s his eleventh birthday.

Buck up, kid. You’re about to get one hell of a birthday present!

Two Countries Separated by a Common Language

In this chapter as in the previous, some of the words used for Dudley’s belongings are different: “cine-camera” in the UK edition, “video camera” in the US; “remote-control aeroplane” in the UK edition and “remote control airplane” in the US.

In the same first paragraph where the toys are mentioned, the phrase “first time out on his racing bike” appears in the UK edition. The word “out” is inexplicably removed in the US version.

Dudley and his friends engage in “Harry-hunting” in the UK edition, and “Harry Hunting” in the US.

Stonewall High, the school that (in theory, ha) Harry’s headed for, is called the “local comprehensive” in the UK edition. In the US, it’s “the local public school”. Interesting that in both, the name of the school is Stonewall High–given that in the US, a high school is either grades 9-12 or 10-12, depending on where you live in the country. Either way, it’s an older age range than Harry, who’s 11 in this book. Harry’s age in the US would put him into either a middle school or a junior high school, again depending on where you live in the country.

On a related note, in the UK edition, it says “Dudley had a place” at Smeltings; in the US edition, it says “Dudley had been accepted”.

The UK edition uses the term “letter-box” for the slot in the door that the post comes through. The US edition uses the term “mail slot”. Likewise, it’s “Get the post, Harry” in the UK edition, but “Get the mail, Harry” in the US.

The boat that the family takes out to the shack is a “rowing boat” in the UK edition, and a “rowboat” in the US.

Five Things About the French Edition

The chapter title in the French edition is “Les lettres de nulle part”, which translates to “Letters from Nowhere”.

The terms used for schools are different in the French edition. Both Harry and Dudley are described as going to “collège”–which is of note since the interpretation of this word for a French speaker is not going to be the same as for an English speaker. Looking this up, “collège” can indeed pertain to secondary school, i.e., junior high, high school, or university. Harry, in particular, is noted as being headed for “collège du quartier”, which I’m taking as the translation for “public school”. “École” is also used later in the chapter, a word I’m more familiar with.

Dudley’s clothes are described with the phrase “ses habits flambant neufs”, which stood out for me since I’m used to thinking of “neuf” as “nine”. Here, it’s used as a translation of “new”. And “flambant neuf”, according to my online dictionary of choice, is specifically “brand new”. And in that paragraph, Petunia calls Dudley “son petit Dudlinouchet”.

“Make Harry do it” becomes “Harry n’a qu’à y aller” in French. And it’s notable that in the description of the mail that arrives, the bill is described with the words “papier kraft”. Which is apparently “kraft paper”, which is apparently actually a specific type of brown paper I never had a term for before. Cool.

When they reach the hotel in their attempt to evade the letters, the hotel owner greets them with “‘Mande pardon”, which is a shortening I hadn’t seen before. I presume it’s a shortening of “Je demande pardon”. Also noteworthy: the address of the hotel in the French edition ends with “Hˆtel du Rail / Carbone-les-Mines”.

French Worldbuilding Terms

Here is where we get the first sign that the name Hogwarts will in fact be translated: the seal on Harry’s first letter has “la lettre « P »”.

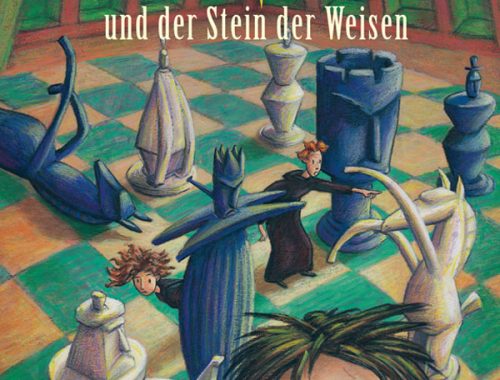

Five Things About the German Edition

Interestingly, Stonewall has “School” added to its name in the German, which does not appear in either of the English editions. It’s a bit weird to see an English word popping out in the midst of all the German, but then, it IS part of a proper noun.

Ha, the German word for toilet is given here as “Klo”. This is apparently slang in the same sense that “loo” is for UK English, or “john” for US.

I think my favorite word in this chapter has got to be “Schokoladenkuchen”–i.e., chocolate cake. Partly because cake! But also because of the rhythm of the word.

The tub that Aunt Petunia uses to dye the clothes is called an “Emailwanne” in the German. This leapt out at me because of the “Email” part of the word–which is, in this case, enamel. And not to be confused with actual email. In that part of the narrative, also, the things she’s dyeing are not identified as old things of Dudley’s, just “a few old things”, “ein paar alte Sachen”.

The German edition changes the song that Vernon hums from “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” to “Bi-Ba-Butzemann”, which is apparently a German’s children’s song. Awesome.

German Worldbuilding Terms

Privet Drive, in German, becomes “Ligusterweg”. And Vernon’s sister Marge, in German, becomes “Magda”.

The seal on the letter from Hogwarts still has an “H” in the German edition.

Onward to Chapter Four–and the coming of Hagrid!